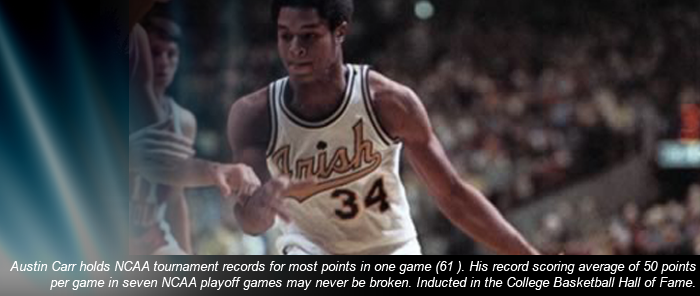

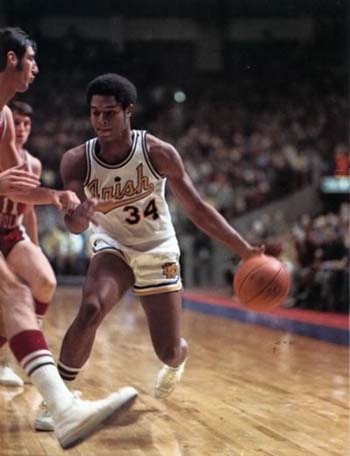

Blast From the Past – Austin Carr

It’s Friday, October 22, 1971. At RFK Stadium, Sonny Jurgensen and the boys in burgundy and gold are 5-0, and The Washington Post is abuzz. On East Capitol Street, the Supreme Court has agreed to hear Curt Flood’s anti-trust case that will eliminate baseball’s reserve clause. In College Park, Abe Pollin, the owner of the NBA Baltimore Bullets, will bring his struggling team to Cole Field House for one night only to showcase the Cleveland Cavaliers’ prized rookie and Washington, D. C. native, Austin Carr. As The Sporting News described Carr, the 1971 Naismith College Player of the Year at Notre Dame, “Inch for inch, he is another Oscar Robertson.” Just take a look. (http://sports.espn.go.com/broadband/videopage?videoId=3235963&categoryId=2459792) Pollin had a problem, though. Carr broke his foot during preseason play. But Pollin was undeterred. He and his staff made the rounds, and Russ White of the Washington Evening Star was waiting. Here’s what he had to say:

VISIT STIRS MEMORIES

CARR: PRODUCT OF PLAYGROUNDS

This area’s best basketball, day in and day out, is performed on the playgrounds. The players are there from morning until night, in the heat of the summer’s day and in the icy winds, which whip furiously over the asphalt of a winter’s evening.

They chatter and shout, and occasionally a shoving match develops because kids at moments take what they are doing quite seriously. They play their pick-up games (winning teams keep playing) or they challenge each other to games of “horse,” the game.

The rules of horse are simple. Make a shot, a difficult one preferably, and the next guy has to make the same shot or he has an “h” on him. When he gets h-o-r-s-e, he is out of the game.

Around the River Terrace community in Northeast Washington, Robert Alstock used to be the king of horse. “No one could beat him,” Austin Carr said. And Carr, pretty good at horse himself, will not forget.

Passes Old Stomping Ground

Carr was home yesterday at his house on 34th St., N. E. He passed by the neighborhood playground he knew in his youth. He saw new kids out playing all the old games. Someone else is today’s king of horse but his basketball fortune, as was Robert Alstock’s, might be no more than the soft drinks and change hustled on the asphalt.

The game remains, however, a way for the city kid to pass his time, to stay off the streets, to emulate a professional hero, and for some it would be a way to escape relative poverty. It was for Carr, who went to Notre Dame and became an All-American and finally signed a $1.2 million professional contract with the Cleveland Cavaliers of the National Basketball Association.

Now the Cavaliers are waiting patiently for Carr’s broken right foot to heal. But yesterday it was the Baltimore Bullets who were squiring Carr around Washington. Angling for attention here, the Bullets shifted tomorrow night’s home date against Cleveland to College Park in the hope that Carr would generate a crowd at Cole Field House. Now all that could be salvaged was to have Carr make some local appearances. Possibly his presence or a few words in print might help sell a few tickets, even if he can’t play.

Basketball is His Game

Basketball, not rhetoric, is Carr’s game. Combine the two, though, and a certain warmth emerges. He relishes recalling what took place on those hot days or icy evenings on the city’s playgrounds.

“Those experiences,” he said, “represent 60 percent of my basketball background. They form every skill I might have. I found myself on the playgrounds.”

Five years ago, 10 years ago, the pick-up games and games of horse all remain vivid in Carr’s mind. “We wasted little time once we got to the courts,” he said. “Sides were already chosen. The guys who lived up above Clay St. were on the uphill team, the guys below Clay [were] on the downhill team. I was with the downhillers.”

“We played other sports, too. Like each Thanksgiving there was the annual uphill-downhill football classic. But basketball was the sport that we played most often—in the spring, the summer, fall and winter. Sometimes, before we played football, we also shot baskets, played horse or something. I was always trying to beat Alstock. It didn’t matter what month it was.”

The River Terrace community had leaders, men whose names Carr rattled off with deep respect: “Mr. Wallace, Mr. Watts, Mr. Rice, Mr. Williams. They were always trying to get us equipment. At times it was tough, but somehow, someway, they managed.”

Wishes He Could Play

“I had an inner drive to make good. But when you’re young, you really can’t think what you are doing is anything more than fun, the thing that you like to do most. At least that’s the way it was with me.”

“I had no idea that the games would get me educated and allow me to have the money to do what I want for my parents today (Austin is buying for his parents, Mr. and Mrs. Austin Carr, Sr., a new home in the 16th and Missouri Ave. area, a fashionable place to be in this city.)

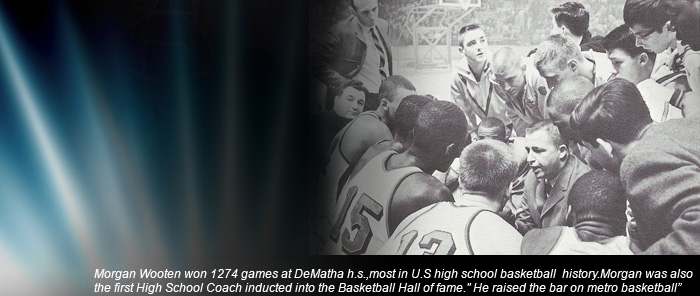

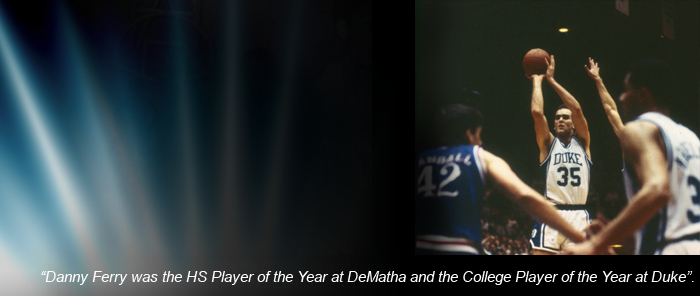

If this young man has a sadness today, it is only temporary. He cannot play tomorrow night. He would like very much to do that. He once helped Mackin High School beat DeMatha High in the same arena. Bashfully, he shrugged his shoulders when Bullets owner Abe Pollin told Austin how much his playing would mean.

“I wish I could play,” Carr said. “I wish I could.”